I mentioned the other day that I just read Bill Schelly's Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America. Since then I've been on a bit of a Kurtzman kick. The nice thing is, most of Kurtzman's work is in print.

I'm going to include some Amazon links here. As always, support your local comic shop or independent bookseller if at all possible, but if for some reason you can't (you don't have a local comic shop, your local bookstore can't order these books, etc.), please feel free to use these Amazon links; as always, they're Amazon Associates links and if you buy through them I'll get a small kickback.

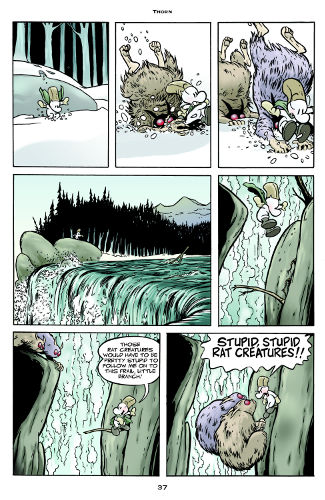

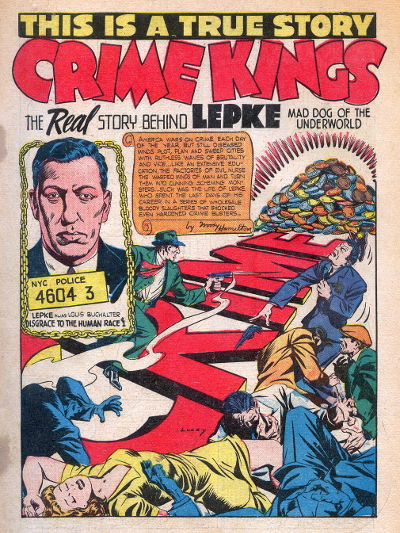

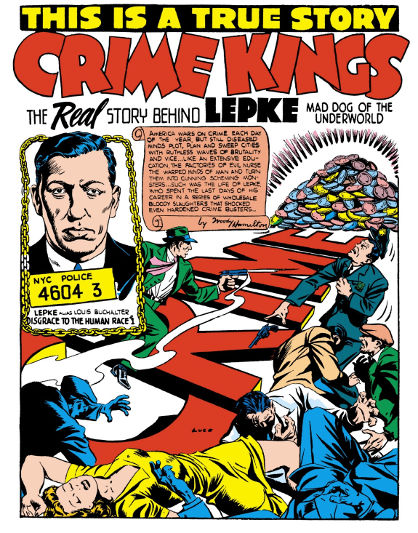

While most of Kurtzman's work is in print, some of his earliest work, sadly, isn't; Hey Look! goes for big bucks used. But his EC work is available in a couple of different forms. Dark Horse has its hardback EC Archives series including Two-Fisted Tales, Frontline Combat, and other titles that feature earlier Kurtzman work such as The Haunt of Fear, Crime SuspenStories, and Weird Science. Fantagraphics has black-and-white collections sorted by artist. Corpse on the Imjin contains some stories that Kurtzman wrote and drew himself, and others that he wrote and laid out but other artists finished. (I think I'll have more to say about Kurtzman's layouts in a later post.) Other books with with Kurtzman's layouts and other artists' finishes include Bomb Run (finishes by John Severin), Aces High (George Evans), and Death Stand (Jack Davis). Some of these books are also available in digital versions. Dark Horse books have DRM, but Fantagraphics books don't.

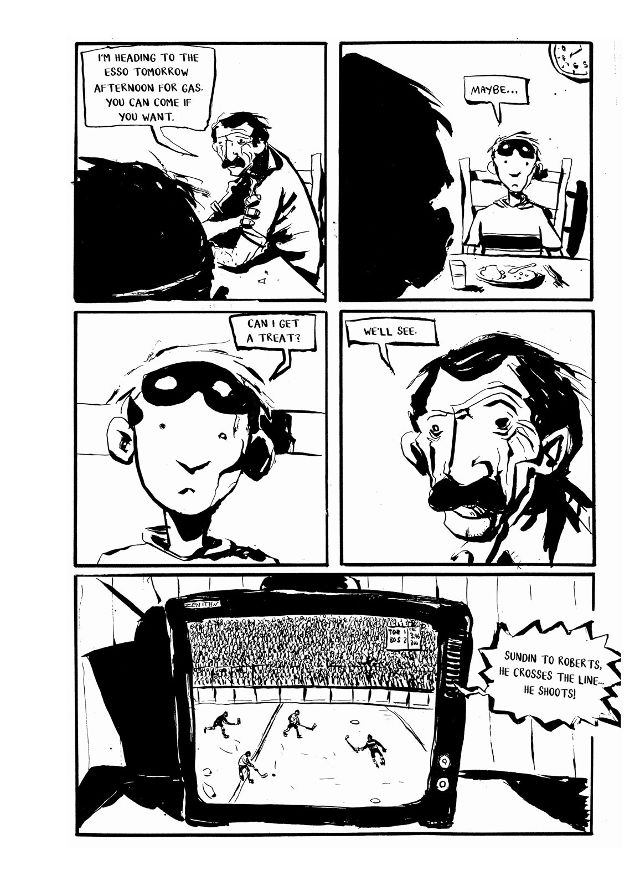

Unfortunately, neither format is ideal. The Dark Horse books are massive hardcovers, fit for a coffee table but not to be thrown in a backpack and taken with you. And I don't care much for the new coloring job. The Fantagraphics books, on the other hand, shrink the art down, and while the black-and-white presentation brings out more detail in the art, I think the stories lose something without their color. Plus, I prefer seeing the stories presented in their original anthology format to seeing them split up by artist. Still, while neither choice is perfect, both choices are good.

Which brings us to Mad. It's available in DC Archives collections, which is the best format you're going to get it in. The original comic book run (and issue #24, the first magazine issue) is collected in a 4-volume DC Archives hardcover set. DC Archives books use original coloring on newsprint. I'm kind of a snob about reprint coloring, and this is my favorite way of doing it: keep the original colors and print on newsprint; that's the way those old comics are meant to be seen.

But a $240 hardcover set is expensive -- even if you could get it for that price, which you can't, because the last two volumes are out of print. They are available digitally, but the digital versions have DRM, and unless you're rocking a 12.9" iPad Pro, you won't be seeing the pages at full size on a tablet. I'm also not sure how the colors look if you put them on a screen instead of newsprint -- and anyway, even the digital versions will set you back a total of $160.

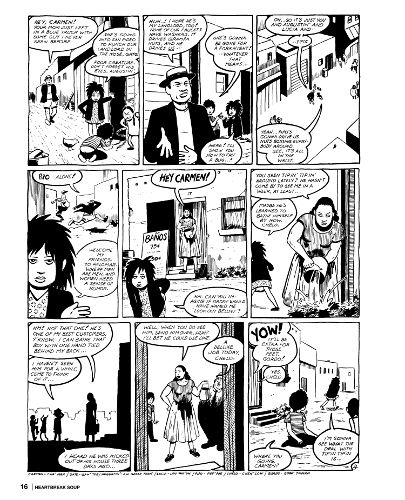

I think Mad's Original Idiots is an acceptable compromise. It's three paperbacks, one each for Jack Davis, Will Elder, and Wally Wood; each book collects its respective artist's work from those first 23 issues of Mad; they go for $15 a pop. It uses the original colors and, while the paper isn't newsprint, it's not glossy, either; the colors look okay.

Again, the format's not ideal. You lose the letters and other editorial content. You also don't get any of the work by anybody but Davis, Wood, and Elder -- and that's a cryin' shame; John Severin is a particularly notable omission, but there were a few features by Basil Wolverton, Bernie Krigstein, Russ Heath, and Kurtzman himself in Mad's comic book period too.

But, nonetheless, I think the Mad's Original Idiots paperbacks are a decent way to go. I've bought all three and have been quite enjoying the Davis one so far. Even with the dated references, even not recognizing what half the parodies are making fun of, they're still great damn comics -- but hell, even when I was reading Mad as a kid in the '90s, I hadn't seen half the movies they were parodying, and I loved them anyway.

After Kurtzman quit Mad, he wrote and drew The Jungle Book, which, contrary to its title, is not based on the Kipling book. It's one of the earliest examples of what came to be known as a graphic novel, and it's all Kurtzman's work. It was reprinted in hardcover in 2014 and was nominated for Eisners for Best Domestic Reprint and Excellence in Presentation.

After The Jungle Book came Trump, Kurtzman's followup to Mad, which featured work by his Mad collaborators (including Elder, Davis, Wood, Severin, and Al Jaffee) as well as humorists including Mel Brooks. It was recently collected and is easy to come by.

After Trump came Humbug, another magazine by the original Mad artists.

Kurtzman's last magazine was Help! There's no complete Help! collection, but there is a collection of the Kurtzman/Elder Goodman Beaver cartoons that were published in it. It's out of print, but doesn't cost too much used.

Kurtzman and Elder's longest-term collaboration was Little Annie Fanny, which was published in Playboy, so that link may be NSFW.

This is not an exhaustive list. There are other Kurtzman books, too, like his adaptation of The Grasshopper and the Ant, From Aargh! to Zap!: Harvey Kurtzman's Visual History of the Comics, and The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics by Denis Kitchen and Paul Buhle.

This list is thorough but not exhaustive; it should be a good starting point, but there are other Kurtzman books out there I haven't mentioned.

I'm not done with Kurtzman. Hell, if the size of this list is any indication, I'm just barely getting started.