The thing that surprised me most, on a replay of FF7 after lo these many years was, you know, it's actually pretty good. Not the best game ever, not even the best Final Fantasy -- hell, not even the best Final Fantasy released in a six-month period --, but pretty good.

It's easy to scoff at it in hindsight, probably because it's not nearly as good as some people claim it is. And frankly I'm embarrassed by my own youthful enthusiasm for it. But, truth be told, it's a good game. And it's not really logically consistent to love 6 and hate 7, because 7 is so clearly a refinement of 6. Amnesiac hero reluctantly joins underground organization fighting an evil, technocratic Empire that is extracting the spirits of a dead, magical race into glowing stones to use for its own nefarious purposes? Yeah, that sounds pretty familiar. The leader of the Empire is killed by a psychopath who is the product of one of its magical infusion experiments gone wrong, and who then becomes the Big Bad? Check. The key to saving the world is a mysterious girl who escaped from the empire's lab and turns out to be the daughter of a human and one of the aforementioned magical race? Mhm. Even the environments and the music are awfully familiar.

Which I suppose in itself could be taken as a knock against FF7 -- it hits a lot of the same beats as its predecessor. But this is Final Fantasy we're talking about. It's not like FF6 was fresh and new -- if you squint, the above plot summary isn't too far off from FF4's, either. And truth be told, 7 does some things better than 6.

It's easy to lose sight of in a flashy, forty-hour game, but, at least in places, FF7 shows a remarkable economy of storytelling. Take President Shinra -- for the first act of the game, he's the presumptive villain, and he makes a hell of an impression. But in truth he only appears in two scenes, I can count his lines of dialogue on my hands, and then he's promptly killed, offscreen, by a character you've never seen and have only heard of in rumors.

That's a pretty far cry from Kefka and Gestahl, really. Kefka is clearly the game's villain from the get-go, and you know sooner or later he's going to take out the Emperor. As for Gestahl, he doesn't get a lot of development but he's in a few scenes and you get a decent sense of who he is.

With Shinra, by contrast, you get a sense of who he is with very minimal information. It's quite well done. And then he's killed just a few hours in, by somebody who hasn't even been introduced yet. That's a shock -- and the presentation, the darkened halls filled with blood, is pretty unexpected too.

The key difference between Shinra and Gestahl -- and the key difference between their respective empires, and arguably between the settings of the two games -- is that Gestahl is an actual head of state, while Shinra is a CEO. The Mayor of Midgar only briefly appears in the game, and makes it very clear that he's a powerless figurehead. The man who runs the reactors rules the world. Forget the motorcycles, that's the most modern thing about FF7.

Shinra's also utterly ruthless and calculating. He wipes out an entire slum and blames it on the terrorists who have been sabotaging his reactors.

(It does fall apart a bit in the Corel flashback. Barrett convinces the people of his town to sell out to Shinra -- and then Shinra burns down the town anyway? I really have no idea how that serves the plot at all. It's not even there to fill the "hero's hometown gets burned down" box on JRPG Bingo, because by that point in the game Sephiroth's already burned Nibelheim, in a different flashback.)

Rufus makes an interesting contrast to his father. For all his initial talk about ruling by fear, his death is a contrast to his father's: the elder Shinra dies after destroying Sector 7; the younger dies saving Midgar. He doesn't have to be there; he could have evacuated, and he chose not to. His deeds redeem him, even if he's still not a very nice person -- and even if Midgar ends up destroyed anyway.

But probably the best example of FF7's skill in economical storytelling is the destruction of Sector 7 and the deaths of Biggs, Wedge, and Jessie. Sure, they're the requisite Star Wars-named fodder characters (Romanized correctly here for the first time!), and no, they don't have that much screentime, but you grow to like them in that short time. You learn just enough about their hopes and their doubts -- Wedge's guilt over the civilian casualties, Jessie's nervousness about her forged ID cards -- to feel for them. And Wedge is a legitimately fantastic example of a character whose personality is communicated visually, through his model and his body language. Which of course starts to bleed into my previous post and the observation that simple, iconic images can convey a whole lot to an audience.

There's a point where the uniqueness of gaming comes into the Sector 7 collapse, too. Sure, killing a bunch of poor people and blaming it on the hero is stock Bond Villain stuff, but this is different: the first opportunity you get to do a little bit of free exploration is Sector 7. You wander around, you meet people, you slowly get introduced to the world of the game there. It's not that the villagers have gotten too much more complicated since welcoming you to Coneria and warning you that the Fire Fiend will burn everything up, but they have little stories and personalities -- hell, the building designs have more character than the people, but the bottom line is that you get a feel for Sector 7 that you don't get for most fodder locations. (Contrast with FF6: Kefka's murder of the population of Doma establishes him as a very bad man, but you're not emotionally invested in Doma or in anyone there except Cyan and his family.) In short, a couple of lines of dialogue, some atmospheric design, and the proper placement in a game's narrative and presentation can really make a minor location stand out.

Oh, and the steel beam through the playground is as subtle as a chainsaw to the face, but it's definitely a memorable image.

And while the game can get awfully overbearing in places, it has some deep themes that are presented without being harped on. Of course the whole thing revolves around Japan's complex relationship with nuclear power -- something thrown into stark relief as I replayed it a few months ago when the Fukushima meltdown was in the news -- and it makes Barrett's team the ostensible heroes, but there are shades of gray there. Barrett is well-meaning, and perhaps the character with the purest motives in the game (leave a better world for the little girl he's adopted) -- but he's also a revenge-obsessed terrorist who gets a lot of people killed, most of them innocent and some of them his own team. And he's easily the most sanctimonious character in the game -- he rants constantly about saving the planet from the monsters who are sucking its lifeblood to generate power, and the game respects our intelligence enough not to point out the irony that he's a former coal miner.

Interface

It's not just the story that feels like an update of FF6; the actual gameplay is really quite similar too. Materia's not so far off from Espers -- the main difference is that it makes the characters even more interchangeable -- and the game is similarly unbalanced. It's still trivial to produce a party that will take the last boss out in a round or two; the game ups his stats a bit if you're at level 98 or 99, but it doesn't really make for a challenge.

There are challenges, of course, for advanced characters -- Huge Materia and the Weapons -- and in this sense, the game is better-rounded than FF6. The biggest problem is that, for the most part, they suck. On my latest play-through, I probably spent about ten hours grinding on Magic Pots and Movers, and for what? Spammy, unsatisfying battles with the Weapons, and a bunch of Master Materia I didn't need.

Seriously, if I ever try to beat Ruby and Emerald on a future playthrough, or get any Master Materia (with the possible exception of yellow), just give me a quick smack in the back of the head. It's stupid and it's a waste of time. And the Arena's not much better.

...but back to the interface. If you don't bother with all the side crap, it's pretty neat! And while weapons and armor have been simplified way down from 6, they complement the Materia system nicely. Do you optimize for equipment stats, for number of Materia slots, for number of linked Materia slots, or Materia growth?

And the Blue Materia are pretty neat too. Added Effect/Hades was always a favorite, and Phoenix/Final Attack is clever if overkill.

Where FF7 runs into its biggest gameplay problems is in simply interacting with the world. It's an early 3D game, and it's obvious that the team was still trying to figure out how to realize the Final Fantasy rules in that context.

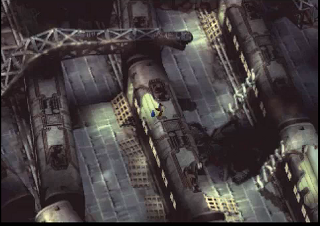

This is most apparent in the field. There is a stunning variety of detailed backgrounds in the game. The trouble is that they're low-resolution, low-color prerenders, and much of the time it's difficult to figure out simple things like where you can walk and where you can't.

Can anybody tell me where the fuck I'm supposed to go on this screen?

There's a toggle you can use to show points of interest, but it's not very useful.

And battle's not much better. In classic Final Fantasy style, it consists of your party in one line and the enemy party in another line, but, for the first time, the characters actually move across the screen when they attack each other -- and the devs thought it would be a good idea to compensate for that by adding movement tracking to the battle interface.

They were wrong.

Say I'm trying to attack a monster, and it moves across the screen while I'm trying to point at it. Well, suddenly it's not where it was a second ago, and I have to move the pointer around to get to it. And probably wind up pointing at my own party somewhere in the process. Or, the reverse -- I'm trying to heal or buff one of my party members, and she jumps across the screen. (Actually it's a pain in the ass to target your own party members even when they're standing still, because the game can't seem to decide whether they're arranged left-right or up-down.)

All of which is just needlessly complicated, seemed-like-a-good-idea naivete. Changing the graphical presentation should not have actually changed the controls! FF7's battle interface is functionally identical to the previous six games'; it should play exactly the same even though it looks different. So that monster's not actually standing in his spot when I point at it? It doesn't matter; if I point at where he was standing a half-second ago it should still target him!

Music

The music in this one is just superb; it's legitimately one of the best original soundtracks in gaming history. Can you remember the first time you heard the boss theme? I can.

If I have one complaint, it's that you can pretty clearly hear Uematsu recycling the same themes at this point in the series -- Aeris's theme sounds a lot like Celes's theme, and they both bear a more-than-passing resemblance to Fanfare for the Common Man.

On the other hand, it's hard to fault Uematsu for retreading musical themes when the game retreads so many story themes -- you can't really blame him for making the Mako Plant sound like Vector when it looks so damn much like Vector too.

Ultimately, I can't take too many points off Uematsu for experimenting with the same riffs throughout the years. Charting his career through the series, it's the story of a guy learning his craft and learning new tools as they develop -- in his chiptune days, he was a programmer as much as a composer. The very first thing you hear in the very first 16-bit Final Fantasy is an extended version of the Prelude theme from the preceding three games. The first thing you hear in 7 is that theme again, this time with harp and vocals.

The move to the PS1 hardware had almost as profound an effect on the audio of the Final Fantasy series as the video. It allowed Uematsu a wide-open world to compose in MIDI, and, in a couple of cases, to use Redbook audio as well. FF6 had already involved some long, complex pieces that went on quite awhile before looping back to the start (Terra's overworld theme being the best example), but 7 had many more. And with instrument samples, the MIDI sounded less artificial than the chiptunes of yore.

The Love Triangle

The biggest problem with the Cloud/Aeris/Tifa triangle is that it's a case of two Bettys and no Veronica. (For you kids out there, you can substitute "Betty and Veronica" with "Edward and Jacob". Probably. I don't know; I couldn't even make it all the way through Steve's summary of Twilight. And it was hilarious.)

Tifa and Aeris are too much alike. At a glance, you expect the obvious trope: the scantily-clad, well-endowed one is the sassy, liberated one, while the conservatively-dressed one is a shy girl-nextdoor type. And at first, the game seems set to go down that path -- after all, you meet Aeris in a church and Tifa in a bar. Then, it takes an interesting turn suggesting that maybe they're about to subvert the trope and reverse the roles, as Tifa turns out to be literally the girl nextdoor and Aeris fearlessly guides you through the slums where she's grown up. But that potential twist never really pays off, and ultimately Tifa and Aeris are both the shy girl nextdoor. There's not a whole lot that distinguishes them from one another, and ultimately the competition between them never really feels like there's anything at stake in it.

Of course, once Aeris gets shish kebabed the triangle is resolved while simultaneously finally achieving a real dichotomy -- Cloud never makes a choice between the two women, the choice is made for him, and the rivalry for the audience's affection is no longer between two sweet girl-nextdoor types but, instead, between the angelic figure who died tragically and the girl who survives, stands by Cloud through his breakdown, and literally follows him to the ends of the earth. That is an interesting contrast, and it's most likely why people still care about Tifa and Aeris all these years later.

And of course there's also the rudimentary romance subquest that served to define them throughout RPG's to come. You can't seriously tell me that any of BioWare's romances are substantially more complex or nuanced than choosing your date for the Gold Saucer. Hell, it's even got a same-sex option!

The Translation

My God.

I played the PC version on my recent playthrough, and the most infamous errors ("This guy are sick", "Off course!/No, way!") were fixed, but there was still a "creek in the floor", and I'm pretty sure I saw "shit" spelled with an apostrophe. And the first boss fight still begins with Cloud instructing you to "Attack while it's tail's up!" -- less notable for the misplaced apostrophe than the omission of the rather nontrivial word "Don't", pretty much guaranteeing everyone playing the game for the first time would die twenty minutes in.

There's an absolutely fantastic peek behind the curtain in The Rise of Squaresoft Localization, an article by Wesley Fenlon at 1up. To wit: the massive script of FF7 was translated by one guy, who had little or no access to the original team, had no "series bible" of common Final Fantasy names and words, and had to hack the whole thing into a foreign character set. Considering that, he did a pretty good job -- I mean, we're still talking about the damn thing, aren't we?

But on the whole it was a big step down from Ted Woolsey's FF6 translation. Sure, that one has its detractors, but I can't for the life of me figure out why. It's got mistakes ("Vicks and Wedge"), truncations ("Fenix Down", "Carbunkl"), and plenty of 1990's-era-Nintendo censorship, but not only does it exceed 7 in its adherence to the basic rules of English spelling and grammar, it's also a lot more fun.

I suspect that FF7 is more like the American FF2 writ large in that people enjoyed it because the deeper themes of its story shone through the lousy script that conveyed them.

Right Time

I think the defining characteristic of FF7 is that it is spectacularly adolescent.

That's not entirely a bad thing -- in fact, it was adolescent in a time when its medium and its audience were adolescent too. It was big, it was operatic, it was bombastic; it was obsessed with its own appearance; it treated its shallow, superficial philosophy as if it were really deep and thought-provoking; it featured awkward cursing and a busty girl nextdoor and in the end it wasn't nearly as damn important as it seemed at the time. In other words, it's pretty damn obvious where its appeal to its target audience came from.